For years, I've always had trouble translating the last three verses of the Torah. It's not because I don't understand the words, but rather because the syntax is bizarre. Most of us simply see the last three sentences as one giant run-on thought, rendering the text:

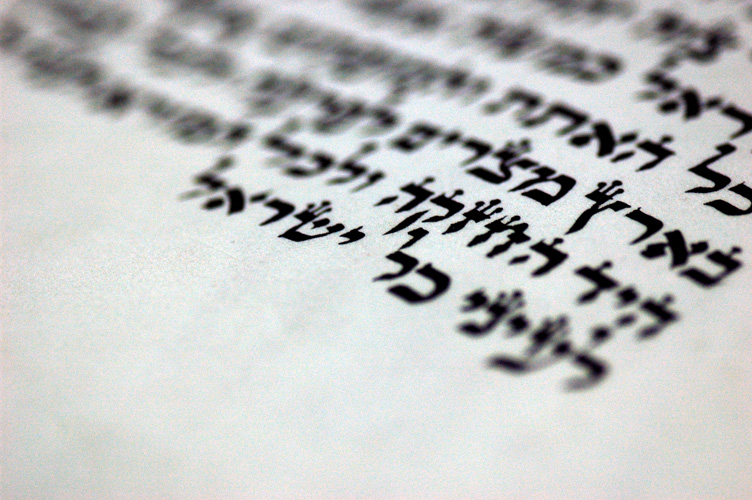

ולא קם נביא עוד בישראל כמשה אשר ידעו יהוה פנים אל פנים לכל האתת והמופתים אשר שלחו יהוה לעשות בארץ מצרים לפרעה ולכל עבדיו ולכל ארצו ולכל היד החזקה ולכל המורא הגדול אשר עשה משה לעיני כל ישראל

Never again has there arisen in Israel a prophet like Moses who knew YHWH face to face (לכל), in regard to all the signs and portents that YHWH sent to him to display in Egypt against Pharaoh and all his servants, and his whole country, (ולכל), and for all of his strength of hand, and for all of his great wonder that which Moses did before the eyes of all of Israel. (Deuteronomy 34).

Remember, the Torah was written without punctuation (it was added later), making its content seem elusive at times. At its best, the Torah ends as it does above, with a poorly constructed Hebrew sentence. We would expect that the most legendary story of all time would––like most classics––end clearly and succinctly. Take for example one of the greatest book endings, F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. The final words are crisp, clear, and offer us closure. Fitzgerald concludes: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

Unlike The Great Gatsby, the Torah's ending throws us a major linguistics hurtle. Whether we translate the word לכל (l'chol) as in "in regard to," or as “for all,” the word appears to begin a new idea separate from the previous line. The Masorah (The 9th Century collection of comments and punctuation of the Bible) recognizes this by adding a sof pasuk, a biblical equivalent of a period, to last word of Deuteronomy 34:10:

: וְלֹֽא־קָ֨ם נָבִ֥יא ע֛וֹד בְּיִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל כְּמֹשֶׁ֑ה אֲשֶׁר֙ יְדָע֣וֹ יְהֹוָ֔ה פָּנִ֖ים אֶל־פָּנִֽים

Never again has there arisen in Israel a prophet like Moses who knew YHWH face to face.

The next line would thus begin a new idea. The problem, however, is that without the previous sentence linked, the last two verses of the Torah leave us with a hanging thought. This would be like an English-language equivalent of having several dependent clauses without having an independent clause; or in other words, an incomplete sentence. The last two verses would thus read:

לְכָל־הָֽאֹתֹ֞ת וְהַמּֽוֹפְתִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֤ר שְׁלָחוֹ֙ יְהֹוָ֔ה לַֽעֲשׂ֖וֹת בְּאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרָ֑יִם לְפַרְעֹ֥ה וּלְכָל־עֲבָדָ֖יו וּלְכָל־אַרְצֽוֹ: :וּלְכֹל֙ הַיָּ֣ד הַֽחֲזָקָ֔ה וּלְכֹ֖ל הַמּוֹרָ֣א הַגָּד֑וֹל אֲשֶׁר֙ עָשָׂ֣ה מֹשֶׁ֔ה לְעֵינֵ֖י כָּל־יִשְׂרָאֵֽל: פ פ פ

For all the signs and portents that YHWH sent to him to do in the land of Egypt, towards Pharaoh, towards all of his servants, and all of the land; and for all of his strength of hand, and for all of his great wonder that which Moses did before the eyes of all of Israel . . .

In this latter reading, there seems to be a thought missing. An ellipsis isn't a part of biblical Hebrew punctuation, but perhaps here it might be in order. We might expect a thought to follow like: “the people would once again come to stray from the ways of YHWH.” Or perhaps a more positive conclusion of “the Israelites needed to leave Moses behind to continue on in their journey.” I have trouble translating the last verse not because it’s a run-on, but because the ending is wanting for a concluding thought.

This year, I became comfortable with a Torah bereft on a logical closing line. Nothing honors the holiday of Simchat Torah more than simply understanding that the Torah ends with an ellipsis. On Simchat Torah, we are reminded that the Torah never really concludes, it only begins anew. Instead of closure, the final words offer us a segue into beginning the never ending story of Torah.